The Guardian: 11 March 2014

Sombath Somphone, a Laotian development worker, was last seen on 15 December, 2012, being bundled into a car at a police checkpoint in Vientiane. He has not been heard from since.

Global campaigns, family pleas and government investigations have found no hint of why Somphone disappeared. Advocacy groups believe he was the victim of an enforced disappearance – that he was detained by the government or government agents, who then deny the action and keep the detainee hidden.

Somphone’s position as a civil society leader working in the field of agricultural development has been raised as a possible factor in his disappearance, but his wife, Singaporean national and former Unicef worker Shui Meng Ng, dismisses any suggestion he worked against the government.

Shui Meng has recently completed a speaking tour of Australian universities trying to dispel inaccuracies which she told Guardian Australia may be endangering Somphone – if he is still being held somewhere.

“There were allegations about him taking a very prominent opposition position to the development agenda of the Laos government,” she told Guardian Australia.

“There were also some allegations that Sombath is not even Laotian, that he’s actually carrying an American passport. I felt it was important to make public and correct many of those misinformations about Sombath, who he is, as well as the type of work he’s doing and his vision for Laos.”

After Somphone disappeared the Laos government told Shui Meng it had established an investigative committee but could not discover anything about his whereabouts.

“The government continues to say that Sombath could have been kidnapped perhaps for reasons of personal conflict or business conflict,” she said.

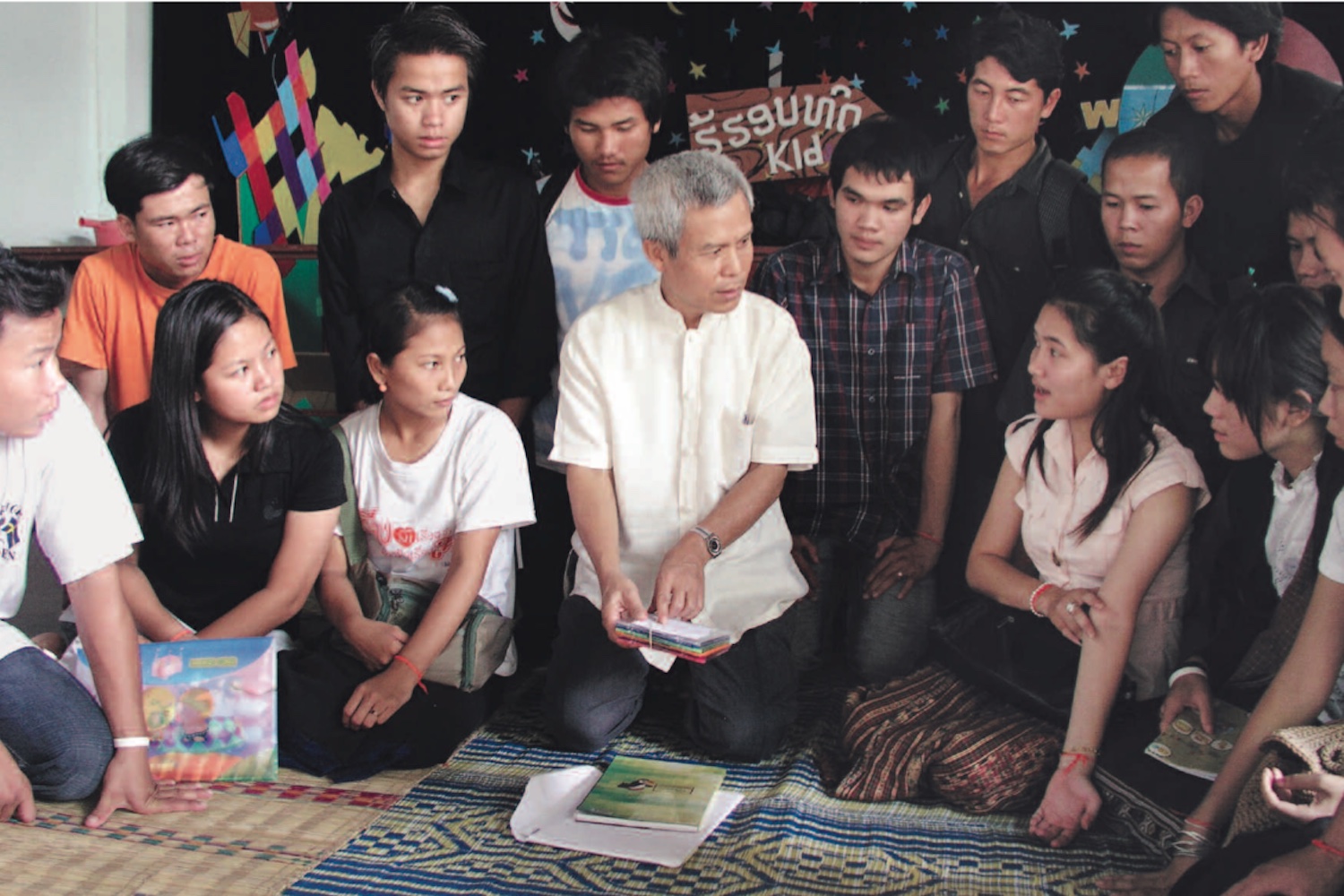

“His work has always been around development, community development, and youth and education development. He has no business contacts or relations at all, and he has no personal enemies that I know of or the family knows of.”

While there have been rumours and theories that Somphone’s work over the past 30 years had caused annoyance within the ranks of the communist government or security agencies, Shui Meng said he was careful to work with the system, not against it.

“I keep wondering why this should happen to him,” Shui Meng said. “He always worked with the government; none of his projects could have been carried out without government approval. That is the nature of things in Laos. All work has to be approved by the government.

“He strongly believes that to get work going in a sustainable way in Laos, it is not enough that well meaning NGOs or local groups just do their own work. It has to engage partners, whether they be government or local committees; it has to sustain the work.”

In recent years the communist nation has loosened regulations against civil society groups and national non-government organisations, and has slowly introduced economic reforms. But it remains a single-party state with little freedom of association, press or political opposition.

During a landmark Asia-Europe people’s forum shortly before he disappeared, documents compiled by Somphone were confiscated and civil society group representatives reported being harassed when they returned to their villages, Rupert Abbott, Amnesty’s Asia researcher, told Guardian Australia. Shui Meng also told Guardian Australia there was an “unexpected” high security presence at the forum.

“Sombath was heavily involved with arranging the civil society forum. It appears that someone within the authorities saw what was happening – civil society coming together – as a threat,” said Abbott.

However, “in terms of Sombath specifically, it’s certainly the case that he was a civil society leader, but to describe him as an activist or to suggest he was kind of clashing with the government is inaccurate.

“He was working within the system. He was an advocate for sustainable development.”

Amnesty International, which has been campaigning for Somphone’s safe return since he disappeared, told Guardian Australia of “frustrations” getting co-operation and information from the Laos government.

International pressure has also failed to result in any progress in the case, but in 2016 Laos will host the Association of South-East Nations (Asean) conference, and a spotlight will be on the country.

“With Sombath’s disappearance hanging over Laos it’s quite difficult to see how Laos is going to be able to pull that off … with this case being unresolved,” said Abbott.

“The clock is ticking for Laos to be able to show that it’s serious about finding a resolution for this case.”

In December 2006 the UN adopted the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. Nearly two years later Laos became a signatory but it is yet to sign it.

A number of high-profile cases such as Somphone’s remain unsolved. Anecdotally, some people are returned a number of years later.

“It’s important in this case and others not to lose hope,” Abbott said.

“When there is an enforced disappearance it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to end in the worst-case scenario. People do turn up again. In Sombath’s case it’s very important to not forget it and to keep putting the pressure on Laos, keep reminding them.”

The Australian government continues to monitor Somphone’s case, a spokeswoman for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade told Guardian Australia. It had expressed its concern directly with Laos authorities on a number of occasions, she said.

“We are concerned that Mr Sombath Somphone disappeared over a year ago and that he remains missing,” she said.

“The Australian government continues to raise concerns about Sombath’s welfare directly with Lao authorities, and to urge the Lao government to redouble its efforts to have him returned safely to his family.”

Shui Meng said: “I’m hanging on to that hope that Sombath will reappear. Hopefully sooner rather the later.”